Adjuntamos artículo de SKYbrary sobre el incidente ocurrido en el Aeropuerto de Zurich (Suiza) el 18 de junio de 2010, en el que estuvieron cerca de colisionar un Avión de Transporte Regional 42-320, operado por Blue Islands Airline, que iba a despegar por la pista 28, y un Airbus A340-600, operado por Thai Airways, que iba a despegar por la pista 16. Se da la circunstancia que ambas pistas se cortan. El accidente lo evitó la tripulación de una aeronave de British Airways, a la espera de realizar el despegue por la pista 28, que alertó a control de la situación.

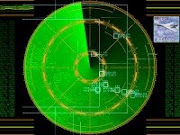

En el esquema siguiente se observa la configuración de las pistas y la maniobra de despegue que iban a efectuar ambos aviones.

ATR 42 Runway Incursion Event

Source: www.skybrary.aero

AT43/A346, Zurich Switzerland, 2010 (RI HF)

Category: Accidents and Incidents

Description

On 18 June 2010, an Avions de Transport Régional ATR 42-320 being operated by Blue Islands Airline on a scheduled passenger service from Zurich to Jersey, Channel Islands, began take off in normal ground visibility and in daylight on runway 28 at Zurich without ATC clearance at the same time as an Airbus A340-600 being operated by Thai Airways on a scheduled passenger service from Zurich to Bangkok began take off from intersecting runway 16 in accordance with ATC clearance. ATC were unaware of this until alerted to the situation by the crew of a British Airways aircraft which was waiting to take off from runway 28, after which the ATR 42 was immediately instructed to stop. It did this in time to clear the runway before the intersection with runway 16 whilst the A340 continued departure on runway 16 in accordance with the issued clearance.

Investigation

A Serious Incident Investigation was carried out by the Swiss AAIB. The FDR and CVR recorders were found to have both been overwritten and therefore of no assistance to the Investigation. However, recordings of all ATC media were preserved and provided sufficient information to conduct a full investigation.

It was established that the ATR 42 had received ATC clearance to taxi to the full length take off position on runway 28 from the south side one minute after the A340 had received ATC clearance to taxi to the take off position on runway 16. However, the ATR 42 had also been previously advised that take off clearance should not be anticipated for a further seven minutes after the line up and wait instruction. A British Airways aircraft was stationary at the runway 28 holding point on the north side of the threshold at this time. One minute after the ATR 42 had received line up clearance, the A340 on runway 16 had been given take off clearance and read it back before starting to roll. Unknown to ATC, the ATR 42 flight crew had also wrongly read back the take off clearance as being for them and begun to roll on runway 28. The British Airways crew had heard the A340 readback but had also heard the words “cleared for take off” from a distinctively different voice and when the ATR 42 began take off, had called TWR to alert them to the apparent risk of simultaneous take offs. It was noted that “the reaction of the (TWR) controller to the (this) report…..was immediate and resolved the situation”. It was found that the ATR 42 had been accelerating through 54 knots when told to stop and had reached a speed of 74 knots before beginning to decelerate. It had been able to clear the runway at a point 950 metres along the 2500 metre long runway and approximately 750 metres prior to the intersection of runway 28 with runway 16. The A340 had continued take-off on runway 16 and proceeded as planned to destination.

LSZH Aerodrome chart for illustration purposes ONLY.

In respect of the lack of situational awareness of the ATR 42 crew, it was considered that their failure to appreciate that the take-off clearance was unlikely to be for them was “surprising, since the take-off clearance from the air traffic controller both included the radio callsign and named runway 16”. It was also noted that they had been on the TWR frequency for nearly three minutes prior to their line up clearance and had also been advised at frequency transfer “that they could expect a take-off clearance in seven minutes”. Had they been monitoring other transmissions on the TWR frequency, it was considered that they would have recognised that another aircraft had received a conditional clearance to taxi onto runway 16 and was also awaiting a take-off clearance, especially as the previous clearance to taxi onto runway 16 was subsequently repeated without condition. Finally, since the radio transmission by the ATR 42 accepting take off clearance was shorter than the parallel transmission made by the A340, it was concluded that the end of the read back from the latter would have been “clearly audible to the (ATR 42) crew after releasing (their) microphone button”.

In respect of the crucial role of the British Airways aircraft in mitigating the potentially disastrous consequences of the error made by the ATR42 crew, the Investigation commented:

“The conflict situation caused by the simultaneous take-offs on two intersecting runways was recognised by the crew of (the British Airways aircraft) and reported without delay to aerodrome control, which had not detected the impending danger. This behaviour shows that the flight crew had a very good overview of the situation. This may have been facilitated by careful monitoring of the radio traffic, the realisation that there had been a double transmission and an active intellectual engagement with the problem posed by intersecting runways.”

In respect of the absence to the TWR controller of any sign if simultaneous transmission of take off clearance acceptance, the Investigation noted that:

“Air traffic controllers questioned were of the unanimous opinion that they would recognise a multiple transmission due to a superimposed whistling tone. This opinion is based on experience with older aircraft-side transmission equipment, which in the event of dual transmission generally caused a superimposed whistling tone in the receiver in the audible frequency range. However, this is no longer the case with modern transmitters equipped with frequency synthesizers, because these transmit very precisely on the nominal carrier frequency. However, this does cause a superimposed whistling tone (but it) is below the audible range of human hearing.”

It was also noted that the automatic selection of ground receiver location for the feed of each aircraft transmission to TWR had significantly favoured the relatively stronger signal from the A340 over the simultaneous one from the ATR 42.

In respect of ground safety nets available to ATC, it was noted that as part of the upgrade of the A-SMGCS to Stage II, a RIMCAS system had been introduced on 31 May 2010 which might been expected to have given a useful warning to the TWR of the conflict. However, it was found that a Stage 2 RIMCAS Alert had not been activated until the ATR 42 had already started to reject their take off and was moving at 61 knots and the A340 was accelerating through 71 knots. This was because this activation required that both aircraft must be, on the basis of the calculated projection, in the "critical circle". It was calculated that if the ATR 42 had not rejected its take off, then a Stage 2 RIMCAS alert would only have been triggered when the accelerating ATR 42 was “in the critical speed range for aborting take-off”.

It was noted that at the time of the incident, a building programme was under way in and around the TWR VCR which caused an obstruction to the view towards the threshold of runway 28 and caused abnormal changes in the background noise level. However, whilst a specially installed telephone hotline had been installed to report any interference caused by construction work, this had not been used in the period prior to the investigated event.

The Conclusion of the Investigation was that:

(this) serious incident is attributable to the fact that on runway 28 the crew of an aircraft initiated a take-off without a corresponding clearance; this led to a significant risk of collision with an aircraft taking off on runway 16.

It was found that the following factors contributed to the serious incident:

• The crew of the aircraft on runway 28 did not notice the readback of the take-off clearance by the crew of the aircraft on runway 16.

• The readback of the presumed take-off clearance by the crew of the aircraft on runway 28 was not audible to the air traffic controller because the chosen location of the receivers of the normal radio operation system favoured the suppression of this clearance.

• Air traffic control did not notice the aircraft beginning its take-off roll on runway 28.

• The air traffic control conflict alert system was inappropriate for defusing the impending conflict.

It was also noted that “the occurrence of the serious incident was favoured by the complex operation on two intersecting runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic”.

One Safety Recommendation was made as a result of this Investigation:

• The Federal Office of Civil Aviation should ensure that double transmission is detectable on the radio operation systems used in Switzerland. (No. 439)

Safety Action noted by the Investigation to have been taken since the occurrence included:

• Following advice from ANSP Skyguide to the airport operator that construction above ground level should be subject to the same procedure as underground civil engineering works so as to ensure that potential impact on TWR operations caused by work on superstructures is always foreseen, a new process was introduced on 1 April 2011.

• The usefulness to ATC of the SAMAX/RIMCAS system which had been introduced shortly before the incident was reviewed and the settings subsequently adjusted. The possibility of a slight increase in nuisance alerts until a corrective software modification, which was expected to be available by the end of 2011 was accepted.

The Final Report of the Investigation No. 2113 by the Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau was published on 8 September 2011. The event was categorised by the Swiss AAIB as an ICAO Category ‘A’ AIRPROX (a high risk of collision).

Related articles and further readings were not included but are available in the skybrary article.

El incidente fue provocado por fallos humanos, el primero y más importante de la tripulación del ATR 42 que consideró que el mensaje iba dirigido a ellos, y el segundo de los controladores que no vieron cómo las dos aeronaves iban directas al encuentro en la intersección de las pistas 16 y 28, y no lo vieron por las obras que se estaban realizando dentro y alrededor de la torre de control y que impedían la visión normal del umbral de la pista 28, además del ruido ambiente que provocaba la misma y que seguramente no permitía tener la concentración y atención que requiere su trabajo. Y se evitó la tragedia gracias a la tripulación del avión de British Airways que alertó al control.

De la información que se ofrece en el artículo de SKYbrary extraemos unos párrafos que tienen un especial significado pensando en la peligrosa operación implantada en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas:

The British Airways crew had heard the A340 readback but had also heard the words “cleared for take off” from a distinctively different voice and when the ATR 42 began take off, had called TWR to alert them to the apparent risk of simultaneous take offs.

It was also noted that “the occurrence of the serious incident was favoured by the complex operation on two intersecting runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic”.

Recordamos que en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas se llevan a cabo Operaciones Simultáneas y Segregadas en Pistas Cruzadas (las prolongaciones de los ejes de las pistas 32/14 se cruzan con los ejes de las pistas 36/18), lo que implica un riesgo cierto de colisión entre aeronaves que despegan y las que aterrizan y podrían frustrar (recordamos que toda operación de aterrizaje en ILS categoría II y III lleva implícita un despegue.)

La diferencia con Zurich es que la colisión tendría lugar en el campo de vuelo y los aparatos podrían caer en cualquier lugar a unos kilómetros del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas, lo que es un riesgo para las poblaciones del área de influencia, incluida la capital Madrid.

Este riesgo que lo evita la Normativa de OACI en su Anexo 14, diseñando pistas paralelas o casi paralelas (inexistentes en el nuevo Barajas), está además contemplado en el propio Plan Director en su Anexo XIII/Anexo II al hablar de cálculos de procedimientos operativos en el que expresamente se especifica que en configuración norte "Las aproximaciones frustradas directas a las pistas 33R bloquean a las salidas por las pistas 36R y 36L". En configuración sur …"las llegadas a la pista 18L bloquean las salidas por la 15R y 15L." Este riesgo podría resultar agravado por el hecho de que en las 4 pistas sus umbrales para los aterrizajes hayan sido acortados en 500 y 1.050 metros como medida de restricción operativa para paliar el ruido sobre Santo Domingo (en configuración sur) y San Fernando de Henares y Coslada (en configuración norte).

Además, y recordando que este riesgo se agrava en caso de un gran volumen de tráfico aéreo como es el caso del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas:

De respetarse por la actual operatividad del aeropuerto los tiempos de bloqueo establecidos en el Plan Director (normativa al parecer propia de la DGAC y no de OACI), en la que extrañamente los tiempos aparecen como distancias, está claro que jamás se podrán alcanzar las 120 operaciones por hora contempladas desde que se inició el Plan Barajas, por otra parte ridículas si se compara con la capacidad de un aeropuerto con CUATRO PISTAS PARALELAS (por ejemplo Charles de Gaulle en París). Por este motivo y dado que hasta en la Resolución de 27 de enero de 2006 por la que se autoriza la puesta en funcionamiento de las 2 nuevas pistas la finalidad de la ampliación es aumentar el número de operaciones con respecto a las llevadas a cabo antes de la ampliación nos tememos que esta aumento de capacidad sólo podrá lograrse a base de violentar peligrosamente aún mas las operaciones segregadas simultáneas. AENA todavía no ha confirmado si realmente se están haciendo operaciones segregadas simultáneas y si se están respetando los tiempos (DISTANCIAS) de bloqueo previstos en el Plan Director para evitar colisiones de aeronaves.

Además en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas se dan varias circunstancias agravantes y concurrentes. Por un lado la presión a la que someten a los controladores, sin importar la fatiga que soporten. Quien considere que los tiempos de trabajo y de descanso son demasiado laxos o benévolos, habría que recordarles que el trabajo que desempeñan requiere la máxima atención en todo momento, y que un error o descuido puede ser fatal. Por otro lado la falta de visibilidad, reconocida en el AIP de los umbrales de las pistas y que es suplida con cámaras.

Desde Las mentiras de Barajas insistimos: Los fallos humanos han sucedido, suceden y siempre sucederán; la mejora de lo que esté mal y no se sepa evitará los incidentes o accidentes futuros; pero lo que está mal y se sabe ahora será causa en los accidentes futuros.

No nos gustaría, y no dejaría en buen lugar a muchos, que fueran los de British quienes pusieran orden en la operación del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas, cuando todos saben lo que se cuece en sus pistas, ni tampoco leer en un informe:

The occurrence of the serious accident was mainly due to the complex operation on two crossing runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic, as in Madrid-Barajas International Airport.

En el esquema siguiente se observa la configuración de las pistas y la maniobra de despegue que iban a efectuar ambos aviones.

ATR 42 Runway Incursion Event

Source: www.skybrary.aero

AT43/A346, Zurich Switzerland, 2010 (RI HF)

Category: Accidents and Incidents

Description

On 18 June 2010, an Avions de Transport Régional ATR 42-320 being operated by Blue Islands Airline on a scheduled passenger service from Zurich to Jersey, Channel Islands, began take off in normal ground visibility and in daylight on runway 28 at Zurich without ATC clearance at the same time as an Airbus A340-600 being operated by Thai Airways on a scheduled passenger service from Zurich to Bangkok began take off from intersecting runway 16 in accordance with ATC clearance. ATC were unaware of this until alerted to the situation by the crew of a British Airways aircraft which was waiting to take off from runway 28, after which the ATR 42 was immediately instructed to stop. It did this in time to clear the runway before the intersection with runway 16 whilst the A340 continued departure on runway 16 in accordance with the issued clearance.

Investigation

A Serious Incident Investigation was carried out by the Swiss AAIB. The FDR and CVR recorders were found to have both been overwritten and therefore of no assistance to the Investigation. However, recordings of all ATC media were preserved and provided sufficient information to conduct a full investigation.

It was established that the ATR 42 had received ATC clearance to taxi to the full length take off position on runway 28 from the south side one minute after the A340 had received ATC clearance to taxi to the take off position on runway 16. However, the ATR 42 had also been previously advised that take off clearance should not be anticipated for a further seven minutes after the line up and wait instruction. A British Airways aircraft was stationary at the runway 28 holding point on the north side of the threshold at this time. One minute after the ATR 42 had received line up clearance, the A340 on runway 16 had been given take off clearance and read it back before starting to roll. Unknown to ATC, the ATR 42 flight crew had also wrongly read back the take off clearance as being for them and begun to roll on runway 28. The British Airways crew had heard the A340 readback but had also heard the words “cleared for take off” from a distinctively different voice and when the ATR 42 began take off, had called TWR to alert them to the apparent risk of simultaneous take offs. It was noted that “the reaction of the (TWR) controller to the (this) report…..was immediate and resolved the situation”. It was found that the ATR 42 had been accelerating through 54 knots when told to stop and had reached a speed of 74 knots before beginning to decelerate. It had been able to clear the runway at a point 950 metres along the 2500 metre long runway and approximately 750 metres prior to the intersection of runway 28 with runway 16. The A340 had continued take-off on runway 16 and proceeded as planned to destination.

LSZH Aerodrome chart for illustration purposes ONLY.

In respect of the lack of situational awareness of the ATR 42 crew, it was considered that their failure to appreciate that the take-off clearance was unlikely to be for them was “surprising, since the take-off clearance from the air traffic controller both included the radio callsign and named runway 16”. It was also noted that they had been on the TWR frequency for nearly three minutes prior to their line up clearance and had also been advised at frequency transfer “that they could expect a take-off clearance in seven minutes”. Had they been monitoring other transmissions on the TWR frequency, it was considered that they would have recognised that another aircraft had received a conditional clearance to taxi onto runway 16 and was also awaiting a take-off clearance, especially as the previous clearance to taxi onto runway 16 was subsequently repeated without condition. Finally, since the radio transmission by the ATR 42 accepting take off clearance was shorter than the parallel transmission made by the A340, it was concluded that the end of the read back from the latter would have been “clearly audible to the (ATR 42) crew after releasing (their) microphone button”.

In respect of the crucial role of the British Airways aircraft in mitigating the potentially disastrous consequences of the error made by the ATR42 crew, the Investigation commented:

“The conflict situation caused by the simultaneous take-offs on two intersecting runways was recognised by the crew of (the British Airways aircraft) and reported without delay to aerodrome control, which had not detected the impending danger. This behaviour shows that the flight crew had a very good overview of the situation. This may have been facilitated by careful monitoring of the radio traffic, the realisation that there had been a double transmission and an active intellectual engagement with the problem posed by intersecting runways.”

In respect of the absence to the TWR controller of any sign if simultaneous transmission of take off clearance acceptance, the Investigation noted that:

“Air traffic controllers questioned were of the unanimous opinion that they would recognise a multiple transmission due to a superimposed whistling tone. This opinion is based on experience with older aircraft-side transmission equipment, which in the event of dual transmission generally caused a superimposed whistling tone in the receiver in the audible frequency range. However, this is no longer the case with modern transmitters equipped with frequency synthesizers, because these transmit very precisely on the nominal carrier frequency. However, this does cause a superimposed whistling tone (but it) is below the audible range of human hearing.”

It was also noted that the automatic selection of ground receiver location for the feed of each aircraft transmission to TWR had significantly favoured the relatively stronger signal from the A340 over the simultaneous one from the ATR 42.

In respect of ground safety nets available to ATC, it was noted that as part of the upgrade of the A-SMGCS to Stage II, a RIMCAS system had been introduced on 31 May 2010 which might been expected to have given a useful warning to the TWR of the conflict. However, it was found that a Stage 2 RIMCAS Alert had not been activated until the ATR 42 had already started to reject their take off and was moving at 61 knots and the A340 was accelerating through 71 knots. This was because this activation required that both aircraft must be, on the basis of the calculated projection, in the "critical circle". It was calculated that if the ATR 42 had not rejected its take off, then a Stage 2 RIMCAS alert would only have been triggered when the accelerating ATR 42 was “in the critical speed range for aborting take-off”.

It was noted that at the time of the incident, a building programme was under way in and around the TWR VCR which caused an obstruction to the view towards the threshold of runway 28 and caused abnormal changes in the background noise level. However, whilst a specially installed telephone hotline had been installed to report any interference caused by construction work, this had not been used in the period prior to the investigated event.

The Conclusion of the Investigation was that:

(this) serious incident is attributable to the fact that on runway 28 the crew of an aircraft initiated a take-off without a corresponding clearance; this led to a significant risk of collision with an aircraft taking off on runway 16.

It was found that the following factors contributed to the serious incident:

• The crew of the aircraft on runway 28 did not notice the readback of the take-off clearance by the crew of the aircraft on runway 16.

• The readback of the presumed take-off clearance by the crew of the aircraft on runway 28 was not audible to the air traffic controller because the chosen location of the receivers of the normal radio operation system favoured the suppression of this clearance.

• Air traffic control did not notice the aircraft beginning its take-off roll on runway 28.

• The air traffic control conflict alert system was inappropriate for defusing the impending conflict.

It was also noted that “the occurrence of the serious incident was favoured by the complex operation on two intersecting runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic”.

One Safety Recommendation was made as a result of this Investigation:

• The Federal Office of Civil Aviation should ensure that double transmission is detectable on the radio operation systems used in Switzerland. (No. 439)

Safety Action noted by the Investigation to have been taken since the occurrence included:

• Following advice from ANSP Skyguide to the airport operator that construction above ground level should be subject to the same procedure as underground civil engineering works so as to ensure that potential impact on TWR operations caused by work on superstructures is always foreseen, a new process was introduced on 1 April 2011.

• The usefulness to ATC of the SAMAX/RIMCAS system which had been introduced shortly before the incident was reviewed and the settings subsequently adjusted. The possibility of a slight increase in nuisance alerts until a corrective software modification, which was expected to be available by the end of 2011 was accepted.

The Final Report of the Investigation No. 2113 by the Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau was published on 8 September 2011. The event was categorised by the Swiss AAIB as an ICAO Category ‘A’ AIRPROX (a high risk of collision).

Related articles and further readings were not included but are available in the skybrary article.

El incidente fue provocado por fallos humanos, el primero y más importante de la tripulación del ATR 42 que consideró que el mensaje iba dirigido a ellos, y el segundo de los controladores que no vieron cómo las dos aeronaves iban directas al encuentro en la intersección de las pistas 16 y 28, y no lo vieron por las obras que se estaban realizando dentro y alrededor de la torre de control y que impedían la visión normal del umbral de la pista 28, además del ruido ambiente que provocaba la misma y que seguramente no permitía tener la concentración y atención que requiere su trabajo. Y se evitó la tragedia gracias a la tripulación del avión de British Airways que alertó al control.

De la información que se ofrece en el artículo de SKYbrary extraemos unos párrafos que tienen un especial significado pensando en la peligrosa operación implantada en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas:

The British Airways crew had heard the A340 readback but had also heard the words “cleared for take off” from a distinctively different voice and when the ATR 42 began take off, had called TWR to alert them to the apparent risk of simultaneous take offs.

It was also noted that “the occurrence of the serious incident was favoured by the complex operation on two intersecting runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic”.

Recordamos que en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas se llevan a cabo Operaciones Simultáneas y Segregadas en Pistas Cruzadas (las prolongaciones de los ejes de las pistas 32/14 se cruzan con los ejes de las pistas 36/18), lo que implica un riesgo cierto de colisión entre aeronaves que despegan y las que aterrizan y podrían frustrar (recordamos que toda operación de aterrizaje en ILS categoría II y III lleva implícita un despegue.)

La diferencia con Zurich es que la colisión tendría lugar en el campo de vuelo y los aparatos podrían caer en cualquier lugar a unos kilómetros del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas, lo que es un riesgo para las poblaciones del área de influencia, incluida la capital Madrid.

Este riesgo que lo evita la Normativa de OACI en su Anexo 14, diseñando pistas paralelas o casi paralelas (inexistentes en el nuevo Barajas), está además contemplado en el propio Plan Director en su Anexo XIII/Anexo II al hablar de cálculos de procedimientos operativos en el que expresamente se especifica que en configuración norte "Las aproximaciones frustradas directas a las pistas 33R bloquean a las salidas por las pistas 36R y 36L". En configuración sur …"las llegadas a la pista 18L bloquean las salidas por la 15R y 15L." Este riesgo podría resultar agravado por el hecho de que en las 4 pistas sus umbrales para los aterrizajes hayan sido acortados en 500 y 1.050 metros como medida de restricción operativa para paliar el ruido sobre Santo Domingo (en configuración sur) y San Fernando de Henares y Coslada (en configuración norte).

Además, y recordando que este riesgo se agrava en caso de un gran volumen de tráfico aéreo como es el caso del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas:

De respetarse por la actual operatividad del aeropuerto los tiempos de bloqueo establecidos en el Plan Director (normativa al parecer propia de la DGAC y no de OACI), en la que extrañamente los tiempos aparecen como distancias, está claro que jamás se podrán alcanzar las 120 operaciones por hora contempladas desde que se inició el Plan Barajas, por otra parte ridículas si se compara con la capacidad de un aeropuerto con CUATRO PISTAS PARALELAS (por ejemplo Charles de Gaulle en París). Por este motivo y dado que hasta en la Resolución de 27 de enero de 2006 por la que se autoriza la puesta en funcionamiento de las 2 nuevas pistas la finalidad de la ampliación es aumentar el número de operaciones con respecto a las llevadas a cabo antes de la ampliación nos tememos que esta aumento de capacidad sólo podrá lograrse a base de violentar peligrosamente aún mas las operaciones segregadas simultáneas. AENA todavía no ha confirmado si realmente se están haciendo operaciones segregadas simultáneas y si se están respetando los tiempos (DISTANCIAS) de bloqueo previstos en el Plan Director para evitar colisiones de aeronaves.

Además en el Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas se dan varias circunstancias agravantes y concurrentes. Por un lado la presión a la que someten a los controladores, sin importar la fatiga que soporten. Quien considere que los tiempos de trabajo y de descanso son demasiado laxos o benévolos, habría que recordarles que el trabajo que desempeñan requiere la máxima atención en todo momento, y que un error o descuido puede ser fatal. Por otro lado la falta de visibilidad, reconocida en el AIP de los umbrales de las pistas y que es suplida con cámaras.

Desde Las mentiras de Barajas insistimos: Los fallos humanos han sucedido, suceden y siempre sucederán; la mejora de lo que esté mal y no se sepa evitará los incidentes o accidentes futuros; pero lo que está mal y se sabe ahora será causa en los accidentes futuros.

No nos gustaría, y no dejaría en buen lugar a muchos, que fueran los de British quienes pusieran orden en la operación del Aeropuerto de Madrid-Barajas, cuando todos saben lo que se cuece en sus pistas, ni tampoco leer en un informe:

The occurrence of the serious accident was mainly due to the complex operation on two crossing runways, which has only a small error tolerance in the event of a high volume of traffic, as in Madrid-Barajas International Airport.

1 comentario:

Como siempre, artículazo fabuloso y a su vez espeluznante ¡Enhorabuena!

Dicho esto, como profesional de larga experiencia, matizo desde mi punto de vista algunas de las siguientes consideraciones:

1.- Que por seguridad, en aviación se da por hecho que todas las aproximación no conllevan frustradas, sino que en todas se efectúa esa aproximación de frustrada.

2.- Que ese mismo incidente de Zurich evidentemente provocado por fallos humanos, en Barajas premeditadamente se está provocando de continuo y por cuadruplicado, al haber suprimido en febrero de 2006 la condición sine qua non de paralelismo o casi paralelismo quq tiene que existir entre las pistas en las que se llevan a cabo "operaciones simultáneas" como son las que desde desde esa fecha, y por tanto de manera algo más que terrorífica son las que se llevan a cabo en Barajas.

3.- Que todas las aeronaves que en un aeropuerto estén efectuando operaciones simultáneas, entre si todas tienen que ser INDEPENDIENTES unas de otras para que en el caso de que a una de ellas o a varias a la vez les sobreveniera un Fallo de Comunicaciones Radio, puedan completar la maniobra a que habían sido autorizadas o frustrarla, evitando con esa premisa de paralelismo o casi paralelismo, ademas de cumplir con las más de 70 condiciones que OACI y el RCA exigen, que dichas aeronaves puedan colisionar entre sí.

4.- Que evidentemente desde que en febrero de 2006 en Barajas fueron implantadas las "operaciones simultáneas a pistas cruzadas", tanto la premisa como las más de 70 condiciones exigidas por OACI y el RCA para poder efectuar operaciones simultáneas, automáticamente quedarón derogadas

5.- Que es el Director del Plan Barajas, D. Fernando Mosquera Martinez, el que por escrito asegura que en Barajas la condición de INDEPENCIA entre aeronaves está derogada.

6.- Que para evitar ese algo más que terrorífico riesgo de colisionar entre si las aeronaves con el que en este preciso momento se opera en Barajas y asi desde febrero de 2006 a pesar del accidente de Spanair, en el BOE de 16/12/1999 en el que está publicado el Plan Director de Barajas, en su Volumen I, Anexo XIII/AnexoII están publicadas dos Tablas, con los tiempos de bloqueos aunque solo aparezcan distancias en dichas Tablas, para los despegues que se efectúen en Configuración Norte o en Configuración Sur, ¡¡ojo al dato!!, en el par de pistas 36L o 36R, o en el par de pista 15L o 15R ahora llamadas 14L y 15R, respectivamente.

7.- Que de respetarse los tiempos de bloqueo que están publicados en el BOE, o lo que es lo mismo de respetarse la Ley tal y como está establecida en el Artículo 4.4.16.2 del RCA, el número máximo de operaciones/hora que por Ley repito, se pueden efectuar en Barajas con plenas garantías de seguridad, son de 40 movimientos/hora, 20 arribadas + 20 salidas, todo las operaciones que sobrepasen los 40 movimientos a la hora corren un riesgo más que evidente de colisiones.

8.- El enorme riesgo añadido que supone mantener cerradas a cal y canto todas sus PISTAS CONTRARIA, y por si fuera poco, el mantener suprimidas después de su ampliación todas sus RPZ,s (Runway Protection Zone)

Luis Guil

Publicar un comentario